The lower west side of Manhattan, part of the historic First Ward, was a vibrant, architecturally significant neighborhood before it was completely obliterated by the construction of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and the World Trade Center in the mid-twentieth century. It was also home to the very first Syrian colony in the United States. This blog, a condensed version of a talk I gave at the Skyscraper Museum on September 6, 2016, is an attempt to reconstruct the character of this lost neighborhood.

The western shoreline of lower Manhattan looks very different today than it did when the Dutch and British first arrived; as early as the late eighteenth century, New Yorkers began to fill and expand westward, eventually creating Greenwich, Washington, and West Streets. (Battery Park City is only the most recent addition.) Home construction followed the shoreline, and rows of Late Federal-style townhouses were built on Greenwich and Washington Streets in the first half of the nineteenth century. These houses were spacious: about twenty feet wide, fifty feet deep, 3½ stories plus a high basement, and covered by a steeply-pitched slate roof, very much like the existing Merchant’s House Museum.[1] The kitchen was usually in the basement, there were front and back parlors on the first, raised floor, the bedrooms were on the second and third floors, and the servants slept in the attic. Frank Moss, in his 1897 guidebook The American Metropolis describes the houses on Washington Street as “the mansion residences of leaders of society and business in the New York of fifty years ago.”

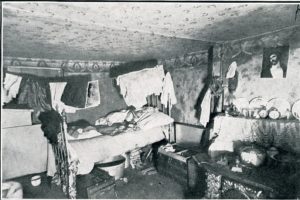

Even before mid-century, the owners began to move to more salubrious neighborhoods uptown, and the houses were gradually converted to rooming houses for incoming Irish, German and Scandinavian immigrants, with the formerly grand rooms broken up into cubicles designed to house the maximum number of residents in the smallest amount of space. By the time the Syrians arrived in 1880, the houses had long been what we would call tenements. The Syrians settled mainly on the east side of Washington Street between the Battery and Albany. There were often four or five unrelated women and men together in one room, making privacy an impossibility. One Syrian reported that on his first night in the city in 1891, he paid a (Syrian) landlord 5 cents for space on a stair landing, which he was forced to share with two others.

Much of the interior of the tenements, including the long stair halls, the stairways, many of the cubicles, and the basement, had no access to light or air, and this was before the advent of electricity. The common areas were filthy, especially around the one sink used by all the tenants on a floor. The privies were in the backyard, built as lean-tos against the fence of the neighboring property, and people had to make their way down several flights to get to them, with only a candle to light the way at night.The façades were heavily altered to allow for commercial activities at street level, with windows enlarged to make shop windows and doors punched through wherever necessary to give access to shops. What had been large stable yards behind the houses were gradually encroached upon with privies or the construction of rentable outbuildings.The once-grand neighborhood had become a slum.

Commercial establishments were primarily located on the west side of Washington, on Battery Place, and on West Street. A score of rooming houses and dozens of restaurants, saloons and beer gardens catered to new immigrants and to the single men who worked on the piers, while the foundries, customs warehouses, coal yards, and shipping agents served the shipping industry itself.

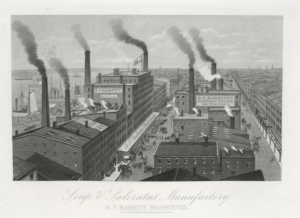

A number of large structures dominated the neighborhood. The behemoth of the neighborhood was BT Babbitt’s soap factory, founded in 1866. Covering a total of twenty-three city lots on the west and east sides of Washington between Morris and Rector and reaching through to West Street, where the soap was loaded onto ships for transport, the factory produced, according to Babbitt, five million pounds of “Babbitt’s Best Soap” a month. He claimed that his patented iron kettles (“the largest soap kettles in the world”) rendered 250 tons of lard in one boil. The factory’s smokestacks spewed black smoke and gave off a horrible stench twenty-four hours a day, and fires and explosions in the factory made living near it noxious and hazardous.

Another large neighborhood institution was Grammar School 29, which was built about 1893 and took up the whole block on the west side of Washington between Carlisle and Albany. It replaced a coal yard as well as several tenements in which Syrians had lived. The colonists tried to get the powers-that-be to offer English-language classes at the school, but they weren’t successful, so they set up their own small school on the second floor of 95 Washington teaching their children English, geography and American history, and then sending them on to G.S. 29.

The other monster built on the street, and one of the few buildings of that period still standing today, was the 20-story Whitehall Building on Battery Place, completed in 1903, and its 31-story Annex, completed in 1910. Stretching from West to Washington, the two buildings covered more than half the block between the Battery and Morris.

Most of the immigrants who lived in the neighborhood worked on the Hudson piers, in the soap factory, or in the nearby silk mills or catered to those who did. Not the Syrians. Instead, they peddled notions and fancy goods that were given to them on credit by a fellow Syrian. Soon enough, beginning in the late-1880s but more frequently in the 1890s, Syrian men began to set up their own businesses, selling dry goods, groceries or notions from basements that had been opened up to give direct access to the public. They slept among their goods, and both they and their stock were regularly soaked as the Hudson River came up through the dirt floors at high tide.

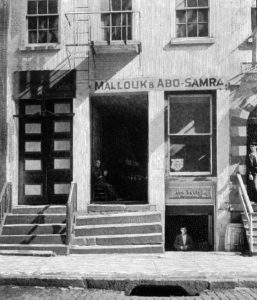

Mallouk & Abo Samra Dry Goods on the parlor floor and John Haddad standing in the doorway of his basement grocery, both 77 Washington Street, 1897.

As they accumulated wealth, they vacated the cellars and began to rent stores at street level or raised three feet above the street; these spaces, relatively safe from flooding, were more expensive than the basements. The parlor floor became the preferred space to house a large grocery store, restaurant (which needed room for tables and chairs and a kitchen), or merchant’s “showroom” and store. The walls separating the front from the back parlor were removed, resulting in narrow, deep spaces. These early Syrian merchants were wholesalers and retailers, providing goods on credit to new Syrian immigrant peddlers and selling oriental goods to tourists. In the photo of Alexander Yazaji’s “grocery” store below, one gets a sense of the depth of the shop as well as of the amazing variety of goods that most Syrian merchants carried: foodstuffs on the shelves behind him, oriental brass lamp shades hanging from the ceiling, water pipes and Turkish coffee pots on the shelves to the right, and what look like straight razors in the glass cases.

If the merchant could afford two spaces, he might rent the parlor floor for his showroom and the basement for his stockroom. This merchant no longer lived among his merchandise, but in rooms above the store, yet often in the same squalid conditions as before. If he had already started a family, they might spread out to fill one or two rooms rather than share with strangers. Some entrepreneurial Syrians rented a whole floor, part of which they sublet to fellow Syrians, as did the “landlord” mentioned above who put one of his fellow immigrants on the stair landing. As they became even more professional and prosperous, Syrian businessmen began to separate entirely their business from their residence. The five-story double warehouse at 60-62 Washington housed many Syrian manufacturing and importing businesses, but not a single residence.

The Syrians living on Washington Street needed Syrian products and services, and their compatriots readily filled those needs. Syrian “rooming houses,” as described above, were among the first businesses, along with Syrian restaurants, which served Syrian food, sold Turkish cigarettes and provided a gathering place to the single men who made up the majority of the colony in the early days. New immigrants continued to operate grocery stores out of basements, and barbershops, pharmacies, banks–even an Arabic record store–sprang up. The street was alive with Arabic sounds, sights and smells. These Syrian-to-Syrian businesses eventually moved to Brooklyn, following the exodus of the colony in the twentieth century, but the wholesalers, manufacturers, importers and larger stores stayed in Manhattan. Every day, like hundreds of thousands of others, Syrians commuted by ferry from their homes in Brooklyn to their offices or stores in downtown Manhattan.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Syrian merchants began to move their businesses uptown to Fifth Avenue between 20th and 30th streets. By 1930, only about 10% of the Syrian businesses in Manhattan remained in the Washington Street neighborhood. Of course, there were always new immigrants to take the Syrians’ place on Washington Street: Greeks, Slavs, and many others filled the tenements, worked on the piers, and frequented the saloons. It was certainly one of the most diverse neighborhoods in New York. But it was razed in the late 1940s to build the entrance to the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, and demolition for the World Trade Center, begun in 1965, finished it off. Now only three buildings on lower Washington Street remain: the 1916 Melkite Church façade at 103; the 1926 community house at 107; and one original tenement building, Number 109. Surrounded on all sides by new high-rise developments, 107 and 109 may not survive, but the group known as The Friends of the Lower West Side are trying to prevent the destruction of these last remnants. “Little Syria, New York,” an exhibition about the neighborhood and its Brooklyn successor, will be opening at Ellis Island on October 1. And a new monument to the Syrian literary legacy will be erected in Elizabeth Berger Park downtown; all will help call attention to this sadly vanished but once-vital neighborhood.

[1] A reconstructed elevation and floor plan as well as photographs of a row of these houses (71-77 Washington) can be found in the Historic American Buildings Survey of 1940 here.