Most early Syrian immigrants to the United States led relatively straightforward lives: they followed a limited number of occupations, practiced the faith of their fathers, married within the community, and had children. Those who strayed from the path make for interesting reading, but someone whose faith, career, and very life were tortuous and veiled in secrecy is someone who demands to be investigated.

Ibrahim G. Kheiralla was born in 1849 in the village of Bhamdoun in Mt. Lebanon of Greek Orthodox parents, but he came under the tutelage of a Presbyterian schoolmaster and may have moved toward Protestantism when young.[1] He enrolled in the first class at Syrian Protestant College (now the American University of Beirut) in 1866 and graduated with four others in 1870. He was a handsome young man (he’s the one second from the right in the photo) and judging by his clothes and demeanor, a bit of a dandy even then.

As so many of his educated countrymen did, he moved to Egypt soon after graduation. He married another Syrian Christian, with whom he had three children, but she died of a miscarriage in 1882. He then married a Coptic Christian whom he quickly divorced, and he sent his children to be cared for by relatives in Syria. His third wife was a Greek widow named Mary Nikolaidis; they brought his three children (and one of hers) to live with them.

Cairo was then the economic center of the region, and Kheiralla was at first moderately successful in business, but in 1888 a lawsuit went against him and he was wiped out, never to recover. In struggling to make a living, he began dabbling in esoteric philosophies, magic, and the “black arts” but was told by an Egyptian clergyman to give up such practices and seek out the Persian merchant Abdul-Karim Tihrani, who was a member and teacher of the Baha’i faith. Baha’is are followers of Baha’u’llah (called “the Bab”—“the Gate”), an Iranian Shi’ite who was, in 1868, exiled and confined to the town of Akka (present-day Acre) in Palestine for his religious teachings. Kheiralla studied with Tihrani for two years, despite the fact that Tihrani spoke little Arabic and Kheiralla spoke no Persian, and Kheiralla converted to Baha’ism in 1890 by pledging fealty to Baha’u’llah.[2] Baha’u’llah died in 1892 and named as his successor his son, Abbas Effendi (called Abdu’l-Baha, “Slave of Baha”) who continued to be held prisoner in Akka.

Anton Haddad, ca. 1896

In Cairo, Kheiralla became friends with another Syrian, Anton F. Haddad, who was a Protestant from Ain Zehalta and an 1882 graduate of Syrian Protestant College. Haddad was working as a translator for the Egyptian Ministry of War.

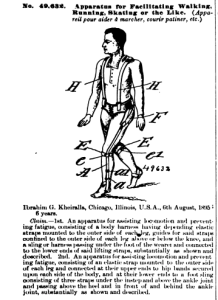

Patent application for walking device

With Kheiralla’s encouragement, the younger man converted to Baha’ism in about 1892. They partnered in a business venture to commercialize some of Kheiralla’s inventions, which included a combination ticket and program book, a special necktie, a walking apparatus to help prevent fatigue (right), a flying machine that imitated the form of a bird, and a device that would prevent a ship from sinking.[3] Kheiralla clearly had a fertile scientific mind, if perhaps an impractical one. In 1892, Haddad went to the U.S. to try to sell the ticket book to the managers of the Chicago World’s fair that was scheduled to open in May of 1893, while Kheiralla traveled to Russia to sell his walking device to the army.

Neither effort succeeded. Kheiralla decided that rather than go back to Egypt, where he had left his family, he would go to America to help Haddad; he arrived in December of 1892, but he also failed to sell the ticket idea. In some desperation, he went to work for a New York Syrian named Abraham Dahrouge; they traveled around the country, Kheiralla giving talks about Egypt and the Holy Land and Dahrouge selling oriental goods after each talk. Kheiralla made a meager living, but he was able to perfect his English and become an adept public speaker. How did his family in Cairo survive while he was traipsing around the world? We don’t know.

This article will conclude next week.

[1] The primary sources for his life and teachings are: Richard Hollinger, “Ibrahim George Kheiralla and the Baha’i Faith in America,” in Juan R. Cole and Moojan Momen, Eds. From Iran East and West: Studies in Babi and Baha’i History. Vol. 2 (Los Angeles, 1984), 95-134; Robert H. Stockman, The Baha’i in America (Wilmette, IL, 1985); and Richard Hollinger, “Introduction,” in Richard Hollinger, ed., Community Histories: Studies in Babi and Baha’i History, vol. 6 (Los Angeles, 1992), vii-xlix.

[2] Hollinger makes the point that Kheiralla, like later converts in the United States, probably did not regard Baha’ism as a religion so much as a set of spiritual beliefs, because he still considered himself a Christian. Richard Hollinger, “’Wonderful True Visions’: Magic, Mysticism and Millennialism in the Making of the American Baha’i Community, 1892-1895,” in John Danesh and Seen Fazel, Eds., Search for Values: Ethics in Baha’i Thought (Los Angeles, 2004-5).

[3] Anton Haddad, “An Outline of the Baha’i Movement in the United States: A Sketch of its Promulgator [Ibrahim Kheiralla] and Why Afterwards Denied His Master, Abbas Effendi,” (New York, 1902). http://bahai-library.com/haddad_outline_bahai_movement. Accessed 1 August 2015.