Unlike the other early Syrian immigrants who have been featured in my blogposts to date, Naoum Mokarzel is well known to scholars and third-generation Syrian-Americans. He was an important publisher, spokesman for his community, and an exemplary man in many ways. What has not been explored is his early life in the United States. Born in the town of Freike in 1864, he was the son of a Maronite priest. After graduating from the Jesuit Université St.-Joseph in Beirut, Naoum, like so many of his contemporaries, moved to Cairo, Egypt, where he taught at a Jesuit college. He returned to Freike in 1886 and established a boarding school in his hometown, but soon left for the United States. Traveling with two relatives—Abdow Rihani, who became a successful merchant in New York and Abdow’s nephew, Ameen Rihani, who became a well-known writer—Naoum arrived in New York on August 4, 1888.

Naoum and the Rihanis settled in the basement of 59 Washington Street in the growing Syrian colony on the lower west side of Manhattan. Like many educated Maronites, Naoum was fluent in French, and he immediately obtained a job teaching the language at the Jesuit St. Francis Xavier’s College (now a high school), located on West Sixteenth Street in Manhattan. Along with his teaching, which must have paid him a meager salary, he worked as a bookkeeper for a number of different enterprises. Abdow was meanwhile peddling and saving money to open a dry goods store at 59 Washington, which he and Naoum did in 1891. It was a “quick failure,” according to Naoum’s niece, Mary Mokarzel.

He went back to Syria for a visit in 1892; when he returned to New York he found that an Arabic-language newspaper, Kawkab America, had appeared, published by the Orthodox Arbeely family. Mokarzel immediately started his own newspaper, Al Asr (The Epoch), with his friend Najeeb Maloof. Maloof was a merchant, so perhaps the capital came from him. No copies of it survive, but it was, according to Mary Mokarzel, produced with gelatin mats, an extremely labor-intensive process, and it lasted less than a year. Even at this young age, Mokarzel held a position of some eminence in the Syrian colony. At an event celebrating the Ottoman sultan in 1894, Mokarzel gave a speech in French to assembled notables, including the Ottoman consul-general of New York, and concluded with a poem of his own making.

During this same time, however, Mokarzel was involved in a number of disputes—both verbal and physical—with other members of the colony, particularly those allied with the Arbeely family; these fights, which originated in personal enmity and journalistic competition, turned into sectarian battles. Mokarzel was arrested several times for slander and assault but never served time in jail.

Then a true scandal erupted. Naoum was named as co-respondent in the divorce proceedings brought by colony member Tannous Shishim against his wife, Sophie. Accusing a woman of adultery was one of the easiest ways to obtain a divorce, and there were set procedures as to how one went about proving the act. Whether the accusation was true or not was irrelevant. However, the Arbeelys’ newspaper gleefully published a transcript of the judge’s decision (in English as well as in an Arabic translation), which besmirched Naoum’s name in the New York colony. Rather than try to defend himself, he and Sophie, now married, fled to Philadelphia, where in 1898, he started what was to become the longest-surviving Arabic newspaper in the United States, Al Hoda (The Guidance). His brother Salloum joined him in the enterprise that same year.

The newspaper, although claiming to be non sectarian, became, like its publisher, a mouthpiece for the Maronite Syrians in the United States and elsewhere. The paper seemed to have been on the wrong side of the Spanish-American war, for example, writing editorials in support of Spain. Whether this was a religious or political stance is not clear, but one suspects the former.

Notwithstanding his role as a Maronite spokesman, scandal continued to dog him. In 1899, he and Sophie published an impassioned defense of their marriage and the divorce that had preceded it in Al Hoda, which suggests that the controversy still swirled around them, even after four years. That same year, Sophie and Naoum separated, and they divorced in 1902. Sophie provided for herself by returning to selling laces and linens in New York resorts. She then moved to Southern California where she opened a linen shop and married a Syrian confectionery manufacturer, and finally after her third husband’s death in 1914, she became a successful real estate developer in California and Hawaii.

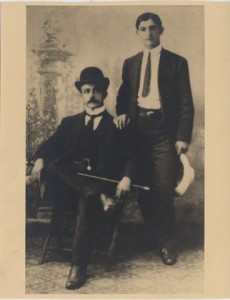

Naoum’s life only became more complicated after his divorce. He and Salloum continued to publish Al Hoda in Philadelphia until 1903, when they moved themselves and the paper to New York. They settled in Brooklyn and opened the newspaper’s office on West Street in Manhattan. In 1904, Naoum married Sa’ada Rihani, Ameen Rihani’s sister, at Ameen’s apartment in Brooklyn. The story surrounding this marriage, as told by Mary Mokarzel, was, to say the least, baroque. She claims that Sa’ada, who was very ill, and perhaps terminal, begged her brother Ameen to grant her one last wish, marriage to Naoum Mokarzel. Ameen relayed that wish to Naoum and he agreed to the marriage. Whatever their real motives might have been, they apparently never lived together, and Sa’ada soon returned to Syria. In 1908, Naoum sued her for divorce in absentia on the grounds of adultery committed in “an inn in the mountains of Lebanon.” The divorce was granted in May, but a ten-year battle ensued in which Sa’ada tried to clear her name and to receive alimony from Naoum. Whether she was successful is not known, but she adamantly maintained that she had never been divorced. She went on to live a long and productive life as a publisher in Syria and was ever after known as “Miss Rihani.”

The sectarian strife within the Syrian community reached its nadir in 1906, when the brother of a Maronite priest was murdered by a fellow Syrian while he was having dinner in a Syrian restaurant on Washington Street. Before the police settled on an Orthodox man as the murderer (Elias Zreik, who was tried and acquitted), Mokarzel was arrested for assault in connection with the murder. The accusation appears to have been motivated solely by malice, and the accuser did not appear at the trial, so the charge was quickly dismissed.

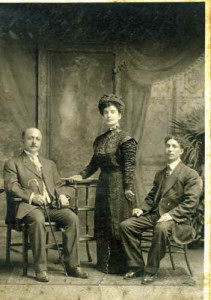

Two years after his divorce from Sa’ada, Naoum married for the third and final time, this time to Rose Bellamah (Abilama), a member of a prominent Maronite family. She was almost twenty-five years younger than Naoum. Judging by her photographs, she was a tightly corseted, upright woman, just the kind of wife a leader of the Maronite community needed at this stage of his career. His political views were frequently aired not only in Al Hoda but in American papers as well, and he represented the American Maronites at the Arab-Syrian Congress in Paris in 1913 (Najeeb Diab, editor of Mera’at al Gharb, represented the Orthodox), where the delegates tried to determine a future for Syria. In 1917, Al Hoda sought and collected more than $30,000 in donations for the “starving people of Mount Lebanon,” which were to be distributed by Mokarzel himself. Half of the money was allegedly directed, not towards the starving, but to support a (Maronite) volunteer force that was gathering to invade Lebanon with the hoped-for assistance of the Allies (the Allies did not cooperate).

The Rihanis and Mokarzel fell out over their different views of the role of France in the future of Syria (influenced too perhaps by the long-running feud between Sa’ada and Naoum). Mokarzel, as the President of the “Lebanon League of Progress,” an American Maronite organization dedicated to establishing a French protectorate in Lebanon, was chosen to serve as its delegate to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The Rihanis became allies of the Maronite Ayoub Tabet, founder of the “Syria-Mount Lebanon League of Liberation” and later briefly the President and Prime Minister of the new state of Lebanon. Because of his earlier stance on the Spanish-American war and his antipathy to Tabet’s organization, which was militantly pro-Ally, Naoum was viewed with suspicion by the U.S. State Department, which questioned his loyalty to America. He was finally, grudgingly, cleared, and issued a passport for Paris.

Never again was his loyalty to be questioned by Americans. On the occasion of the Silver Anniversary of Al Hoda in 1923, Mokarzel was feted as a great leader by the literati of Maronites and non-Maronites alike, as well as by many American friends. His death in 1932 in Paris was the cause of great sorrow in New York, where he was given a large funeral, before being sent to Lebanon to be buried in the family cemetery in Freike. On his death, Salloum took over the publication of Al Hoda, and on his death, in 1952, Salloum’s daughter Mary, despite knowing no Arabic, carried on until its shuttering in 1968.