Why would two seemingly respectable Syrian immigrants be publicly repudiated by their countrymen? As everyone who reads this blog knows, I have an affection for, if not an obsession with, stories that seem to contradict the Syrian myth of success, assimilation, and harmony. In the course of doing research about the early Syrian colony in New Orleans, I came across the fascinating intertwined stories of Nami (or Nebi) Nebham (or Nebhan) and Sarah Marhay (or Merhi), who lived such irregular lives that their fellow Baton Rouge Syrians publicly repudiated them in 1907 and again in 1910. There were well-publicized disagreements that were taking place within many Syrian immigrant communities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, disagreements that were decried by the Syrians themselves. Was this just another instance of this, or were Marhay and Nebham a unique case?

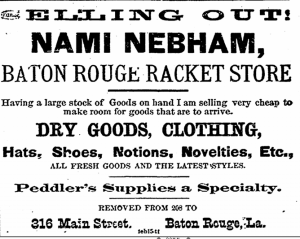

Sarah Faraj Marhay was born in Qartaba, Mt. Lebanon in 1864 and left her husband and son at home when she emigrated in 1890; her son and daughter-in-law followed in 1898, but her husband remained in Syria and died there. Nami Nebham was born in Beirut in 1870 and came with his brother Assad to the United States when he was eighteen. He settled in Jackson, Mississippi, where he was naturalized in 1893, and there married a Syrian woman named Jamilie and had a son. In 1894, the family settled in Baton Rouge; they seem to have been the first Syrians in the city. He took over the “Baton Rouge Racket Store” on Main Street, selling dry goods, clothing, and peddlers’ supplies—everything except rackets.

Nebham was successful: he advertised the Racket Store in the Baton Rouge Advocate every single day, and after only a year, he rented a new store one block east on Main, did extensive renovations, and set up as a jewelry and watch merchant. The Advocate called him a “solid citizen” and “welcomed more of his kind” to come to Baton Rouge. In 1897, he was apparently well off enough to agree to pay the debts of a fellow Syrian, George Zachariah.

Although still married to Jamilie (they are listed together in the 1900 census, but there is no sign of the son, who may have been sent to Syria), Nami established an alliance (or liaison) with Sarah Marhay. She and her son Tony had just opened a dry goods store a block away from Nami’s. What she had been doing in the decade before she opened the store is unclear, but it is likely she was peddling. Known to her American customers as “Miss Sarah” or “Miss Merhi,” Sarah became embroiled in Nami’s troubles.

In the first of many Nebham-Marhay exploits, Nami had somehow obtained power of attorney for an American named Henry Newell, who revoked it publicly and sued Nebham for forgery and embezzlement. Although Nebham countersued for slander and won, his reputation was tarnished. Sarah and Tony were also involved in the dispute and spent some time in jail, as did Nami’s brother Assad; they, like Nami, sued Newell for malicious persecution. Six months later, Nami and Sarah were convicted of assaulting a fellow Syrian named Phillip Sabbagh (who owned a dry goods store next to Marhay’s) and were each fined $5.00. The cause of the affray was not recorded. Nebham was convicted of disorderly conduct for getting into fights several times in the early years of the twentieth century, and he was involved in a dozen lawsuits—sometimes as plaintiff and sometimes defendant—with both Syrians and Americans. Both Nebham and Marhay were frequently fined for violating the Sunday laws (which forbade businesses from remaining open on Sunday), and Nami was fined again for allowing gambling to take place in his store. Sarah brought charges against one George Flowers for shooting at her son; a judge dismissed the case but not without mentioning that he had seen the Marhays in court before.

By 1905, Nami and Sarah had become business partners (“Nami Nebham & Co.”) and were living together above the store at 316 Main Street. She kept her ownership of “S. Marhay and Son,” but let Tony run it. Jamilie disappears from the record; did she go back to Syria to join her son? In 1907, a very public airing of dirty linen occurred when nineteen Baton Rouge Syrians published a “card” in the Baton Rouge Advocate accusing Nami of various offenses, the most serious of which was living in “concubinage” with Sarah. They claimed he had a wife and family in Beirut, which may refer to Jamilie and their son. A relative of Nami’s, David Nebham, took out a separate advertisement laced with sarcasm that said, in essence, “They [Nebham and Marhay] may be married, but not to each other.” (There was bad blood between the two Nebhams going back to at least 1901, when Nami sued David and lost.) Strangely, the Syrians urged a judge to deport Nami from the city or at least confine him to an isolated neighborhood. Although the judge did not comply, he warned Nami that he would be watched closely.

In 1909 both Nebham & Co. and S. Marhay & Son went bankrupt; one cannot help but think that their businesses—like their lives—were intertwined. In the 1910 census, Nami and Sarah were still living together, yet declared themselves single. In the same year, Nami and Tony were convicted together of attacking one Nolan Dougherty with a buggy whip and served 30 days in jail. The Syrians of Baton Rouge once again called for Nebham’s expulsion, listing his misdeeds and again accusing him of living in concubinage with Sarah. As the Advocate put it, “Nebham is charged with possessing a wife and family in the Orient, but with having flagrantly forgotten this fact in Baton Rouge.” In response to the accusations, he told the newspapers that he was living with Sarah because she was the mother of his son-in-law, which was a blatant lie (he had no daughter, much less a son-in-law). Sarah on her part published a notice in the paper claiming she and Nami were married:

“Any person interested may call at 604 Main street and see for themselves that I am not living in concubinage. I will show my marriage certificate duly executed by an authorized officer of the state.” Signed/SARAH MARHAY NEBHAM. Of course even if she possessed such a certificate, it does not disprove the accusation that Nami had a family in Syria.

Remarkably, the day after the Baton Rouge repudiation, and every day for two weeks thereafter, fifty-nine Syrians of the New Orleans colony published a “card” in support of Nebham, saying that the Baton Rouge Syrians had turned against him because, having been recently bankrupt, he was no longer in a financial position to help them. They did not mention Sarah at all. Perhaps because of this show of support, Nami, Sarah, Tony, and Tony’s family all moved to New Orleans in about 1912. Nami became a traveling salesman for a number of companies, including May & Ellis, textiles, and the Bay Shoe Company, journeying frequently to Mexico to sell goods. Tony held a variety of jobs. The Marhays and Nebham had effectively been driven out of Baton Rouge by their fellow countrymen’s very public disapproval.

In the 1920 New Orleans census Sarah and Nami were listed as married. They must have fallen out soon after, though, because in 1922, Nami sued Tony Marhay for slandering him to the owners of Bay Shoe Company, for whom Tony also worked, stating that Tony had a vendetta against Nami because of “Marhay’s mother’s dislike for him [Nebham].” If Nami and Sarah had indeed been married, they must have divorced soon after the census was taken, because in about 1924, he married Maggie Zachariah (the widow of the man whose debts Nami had agreed to pay in 1899). Although no record of the marriage has been found, their 1926 divorce was widely covered in the press. She won $125/month alimony. They re-married, however, in 1928 and lived together until Nami’s death in 1935. He was survived, the newspapers said, not only by his widow and five adopted children, but by his son in Beirut. Neither Jamilie nor Sarah was mentioned. After his death, Maggie reclaimed her widowed name, Zachariah, and lived in Baton Rouge until her death in 1979.

By 1930, Sarah was living alone in New Orleans in a rented room, using the name Marhay again, and working as a housekeeper in a private home. When she died in 1934, her obituary made no mention of Nami.

My thanks go to Meera Mnymneh, a student at Loyola University, New Orleans, for her invaluable research assistance on this article.