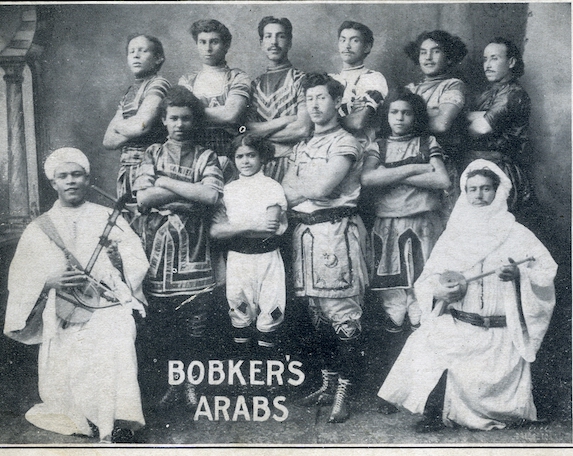

There is a long history of Arabs performing in the United States, beginning before the Civil War when North African acrobatic troupes (some including women) traveled around the East Coast and as far west as Iowa, performing athletic feats and tumbling on vaudeville stages, outdoors, or in tents they set up on vacant land. The exotic costumes, acrobatic style and especially the human pyramid came to be identified with Arabs.

Watch this 30-second clip of Hajji Cheriff performing in Edison’s studio in 1895.

Five Syrians who began as performers–Habib J. Katool, George Jabour, K.G. Barkoot, George A. Hamid, and Namy Salih–went on to become impresarios, producing carnivals, circuses, vaudeville acts, and side shows, employing hundreds of performers, traveling thousands of miles during “the season,” and becoming wealthy in the process. Their flamboyance and constant self-promotion–essential for their success–set them apart from their fellow Syrians. Three are featured in this blog, the others will be covered in a subsequent post.

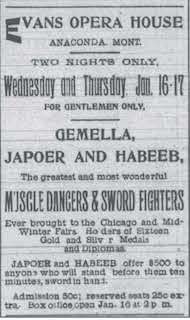

After performing as a swordsman and Bedouin horseman at the 1893 Chicago and 1894 San Francisco World’s Fairs, the Shweir native Habib Katool gathered five of his fellow Syrians–three men and two women–and took them on tour around the West, where they performed sword fighting, acrobatics and belly dancing, by far the biggest moneymaker at the fairs. One of the dancers, Gemella (Jamelie), was reportedly Katool’s wife.

In 1900, following a short stint as manager of a vaudeville theatre in Baltimore, Katool formed a new troupe of thirty men and women, most of whom were not Arabs. Shuttling between street fairs, state fairs, and world’s fairs all over the United States, he set up the same concessions everywhere they went: the Streets of Cairo; a Turkish theatre; a Moorish theatre, and wild animal acts (a Syrian woman performed as the lion tamer and Katool himself became a famous snake handler). The animal acts and belly dancing were his biggest draws. The human acts eventually fell away, but the animal acts remained popular until the company went bankrupt around 1915. Katool went on to manage the monkey act for Tidwell Shows and was traveling with his monkeys when he died in Texas in 1941.

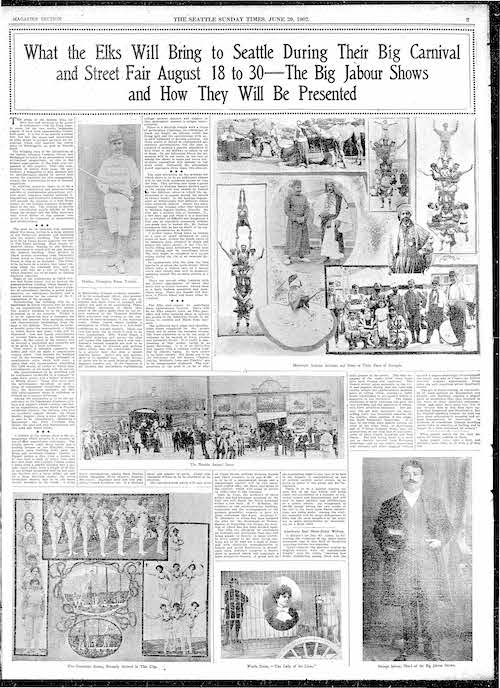

George Jabour also performed at the Chicago and San Francisco World’s Fairs and joined Katool’s first troupe, but in 1898, he went out on his own, building a “Turkish” theatre and a “Turkish” smoking parlor at Coney Island, where he catered to the prurient and orientalist tastes of the American public with belly dancing and exotic decor. He was forced to close after numerous police raids and competition from other oriental attractions, and he took his carnival on the road. The Jabour Carnival and Circus Company became famous: Jabour was credited with singlehandedly creating the Oriental Carnival, with its belly dancers, whirling dervishes, Arab acrobats, and sword fighters, along with animal acts. At one point, he had 125 people working for him. He was, however, plagued with charges of immorality in his female entertainment, and the weather too conspired against him. The company went bankrupt in 1904–all of his Syrian investors lost their money–and he left the entertainment business to start a garment factory in New York. He died in Milford, Pennsylvania, in 1924.

Khalil G. Barkoot claimed to have been the youngest concessionaire at the Chicago fair, but even if true, he went back to Syria and only immigrated in 1896, accompanied by his brother Braheem (who was quickly nicknamed “Babe” by his fellow carneys). They spent some years performing in Streets of Cairo concessions for various carnival companies, and in 1902 they set up their own company. Although it began life as the Oriental Carnival Company, by 1904, they had renamed it K.G. Barkoot Shows, shedding all vestiges of its oriental roots. Generically American in content and presentation, the acts included the Plantation Minstrels, the Italian Concert Band, the “girlie” show, Princess Flora’s Gypsy Camp, Cook’s Jerusalem, and the Electric Theater, where Edison’s The Great Train Robbery was shown on a continuous loop. By 1909, K.G. was fielding two complete carnivals that performed simultaneously in two towns miles apart. The hundreds of performers–women, men and animals–and elaborate sets required a large support staff and twenty rail cars to transport them.

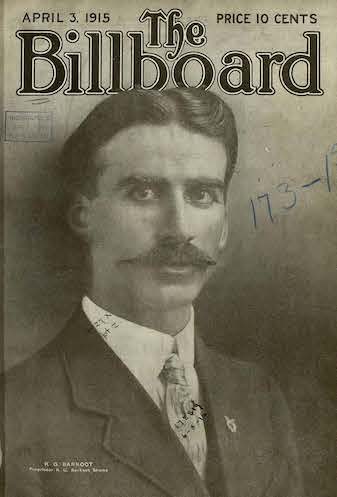

[The 1913 season was] one of the most successful seasons of its career….He has amassed considerable real estate, a healthy bank account, unlimited credit and a 20-car show, one of the finest, best equipt, most progressive and representative organizations of its kind extant, and he is considered by all to be one of the brightest luminaries in the firmament of showmen.

“K.G. Barkoot’s Career,” The Billboard, 29 November 1913, p. 126.

In 1915 Barkoot was featured on the cover of Billboard, his carefully groomed hair and mustache, diamond stickpin, silk tie, and handsome notched-lapel jacket marking his status as one of the most famous and successful showmen of his generation. He leased an entire amusement park in Tennessee that year, a venture he eventually abandoned as being too expensive and risky. 1925 was another banner year for the company–a twenty-five car season–but he was plagued by accusations that he allowed (or encouraged) illegal gambling at his fairs, which led to the arrest of his wife and his brother, who were both running games. Both were released after paying a fine, but his carnival remained under siege. And, as the Depression loomed, the carnival began to suffer losses.

Drastically downsizing. K.G. began limiting the company’s appearances to the Midwest and South and finally to a single city, Toledo, Ohio, where he was living. He died there in 1948, having sold what remained of the business the previous year.