In the spring and summer of 1893, a spectacle such as had never been seen before in America came to life on the shores of Lake Michigan. The Columbian Fair attracted more than twenty-seven million visitors in its five-month run, embodying the proud (some say hubristic), technology-loving, patriotic, orientalist, and self-improving zeitgeist of the late nineteenth century. It also played an outsized role in attracting Middle Easterners, particularly Syrians, to the United States. Hundreds upon hundreds of them came to take part in the fair; many stayed.

Organized to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America—but delayed a year by the enormous logistical challenges facing the organizers—the fair was divided into two sections: the “White City,” so-called because of the color of its buildings; and the “Midway Plaisance,” a mile-long strip that ran northwest from the fair proper. The White City, made up of temporary structures designed by noted architects of the day, represented “a veritable encyclopedia of civilization.” It included thematic installations representing, among much else, manufacturing, the fine arts, and women’s achievements, as well as buildings erected by each of the states, showcasing their agricultural and industrial products. Many foreign countries, including the Ottoman Empire, built grandiose monuments to their own achievements, historical and modern.

The White City was high-minded; the Midway Plaisance low-brow. Originally conceived as a venue for “live ethnological displays,” the Midway came to feature exotic dancers, rides (the Ferris Wheel made its first appearance here), entertainment, food, hucksters, fortune tellers, and displays of beautiful women, all designed to appeal to the common man (and woman). Most of these attractions came to be associated with amusement parks and carnivals of the future, which often included a section called The Midway. It was fashionable for newspapers and the upper class to disparage the Midway’s appeal, yet there was no question as to which part of the fair was the most profitable and influential.

Middle Eastern concessions, representing four regions—North Africa, Egypt, Syria, and the Ottoman Empire—dominated the Midway Plaisance, far outshining other foreign entries like Java and Japan. Only one of these concessions was Arab-owned and operated.

- French entrepreneurs held the concession for the Algerian and Tunisian Village. One, A. Sifico of Algiers, contracted to build an Algerian Concert Hall, as well as a “Tunis street with Tunisian Bazaar,” and an “Algerian Street with Algerian Bazaar.” Parisian Amedée Maquaire received the concession for a Tunisian exhibit and cafe. Maximilian Schmidt, a resident of Tangiers, built a “Moorish Bazaar, a Moorish Dwelling House, and a Moorish Restaurant.” Even a native Chicagoan, Herman Bernhardt, got into the act with his “Moorish Palace,” but there was nothing Moorish about it; it was simply named to entice people to go in.

- An Alexandrian banker and businessman named George Pangalo organized the Egypt-Chicago Exposition Company to fund and build “Cairo Street,” a replica of an Egyptian city street, which became the most profitable and best-known of the fair’s attractions. It offered camel and donkey rides up and down the street; twice-a-day performances of a Muslim wedding and sword fighting; belly dancing in the theater; sweet sellers; dozens of craftsmen demonstrating their skills; and shops selling Egyptian goods.

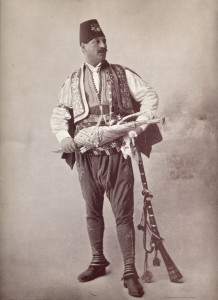

- A Syrian company, Elia, Souhami, Sadallah et Cie, and its sister company, Souhami, Sadallah & Bistani, both based in Constantinople, were behind several Middle Eastern concessions: a “Street Scene in Constantinople [which included a mosque] and Turkish Shops,” a “Tribe of Bedouins,” an “Exhibition of Photographs of Syrian and Turkish Subjects,” and the “Persian Palace,” in which it promised to sell goods of a “distinctively Persian character.” The Bedouins performed every day on horseback in a “Wild East show.”

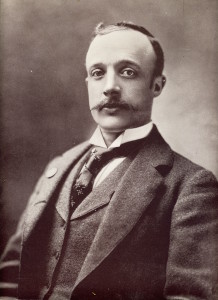

- The Hamidie Company, formed by the Ottoman government to manage its participation on the Midway, built the Turkish Village and Turkish Theater, which were under the management of Robert Levi, a restaurateur from Constantinople. His “fanciful garb” made him an attraction in his own right.

Syrians transcended the regional fiefdoms in a way no other group did. They were the only “native” group who were able to set up a joint company to make the huge investment needed to become concessionaires, and Syrians managed many of the concessions owned by others.The Hamidie Company entertainers, though under Levi’s ultimate direction, were managed by a half-dozen Syrians. Syrian merchants also sold goods in all the Middle Eastern venues. In the Tunisian Village, for example, they offered what were purported to be Tunisian goods alongside Tunisian merchants selling bona fide Tunisian goods; in Cairo Street, they sold “Egyptian goods;” and they sold oriental goods in the Turkish Village. The Syrian concessionaires, ironically, hired Joseph and Yak Oussani, Chaldean Iraqis, to build and manage the Persian Palace, because of the Oussanis’ long-standing trade relationship with Persia.

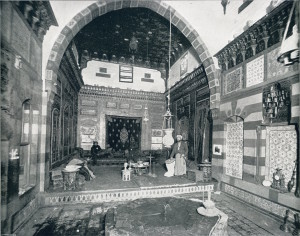

A rare interior shot of a replica of a Damascus merchant’s house, part of the Turkish Village concession

The Chicago Exposition Company, which organized and managed the fair, provided the land, sewerage, gas, electricity, and water, but the huge expense of building these elaborate displays was borne by the concessionaires. The foreign companies either brought materials from the Middle East or were forced to buy them at fair-inflated prices in Chicago. When, at the close of the fair, they tried to recoup some of their costs by selling their buildings and furnishings, they were lucky to get five cents on the dollar; it left a bitter taste.

In addition to materials, the concessionaires were contractually obligated to employ “natives of Turkey [or Algeria or Persia, depending on the venue] in all capacities practicable,” a crucial provision that resulted in the large Middle Eastern presence at the fair. They paid their employees’ passage, chartering ships and filling them with performers, cooks, and “artistes.” The steamship Cynthiana sailed from Beirut carrying more than 200 Sadallah-Souhami and Hamidie employees, while the Guildhall from Alexandria brought Pangalo and his performers to Cairo Street. The concessionaires were also obligated to build dormitories within their concessions for their employees, who were confined to the fairgrounds even when the fair was closed (a rule imposed by the Company).

For the privilege of selling at the fair, the Company charged concessionaires twenty-five percent of gross receipts, a “tax” that was passed on to the merchants and impresarios, in addition to whatever rent or commissions the concessionaires themselves charged those working in their concessions. One can imagine that merchants might have been hard-pressed to cover their costs. The Company also imposed a fifty cent cap on admission prices, which meant that impresarios had to get as many people into their theaters as possible. Thus emerged the “huckster,” who called out to passers-by urging them to experience the exotic entertainments within.

In general, the entertainers were better earners than the merchants. The Egyptian belly dancers, whose gyrations and scanty clothing both scandalized and titillated the fair-going public, were said to have been the most profitable attraction at the fair (I have written about these dancers in my recent book), and there was a trickle-down effect to the Egyptian shops and sweet sellers of Cairo Street. George Pangalo went home a happy man as did many of his employees. One “donkey boy” reportedly went to a Chicago bank after the fair to change his $700 into French francs. The Oussani brothers, who built and staffed the Persian Palace for Souhami, Sadallah & Bistani, cannily responded to the Egyptian competition by reportedly hiring can-can girls from Paris, disregarding their contractual obligation to employ only Persians. Wags began calling it “The Persian Palace of Eros.” This tactic not only increased paid admissions to the Palace, but increased sales of the goods they had brought with them from Baghdad.

Among the merchants, competition for customers was fierce, engendering disputes that had to be mediated by the concession managers. Fistfights were not unheard of. Several Tunisians actually went bankrupt (one reportedly committed suicide at the fair), and the Hamidie Company ended its tenure $30,000 in debt, leaving its employees stranded in Chicago. The Hamidie merchants blamed Robert Levi for this failure, when in fact it was probably due to the competition of nearby Cairo Street, which, with its belly dancers and camel rides, siphoned off much of the fair-going public.

Like many of the others, Syrian merchants saw only modest success at the fair, nothing like what they had dreamed of when they left home. Nevertheless, their experience, especially interacting on a daily basis with American customers, meant that they came away with an understanding of the American market, knowledge that contributed to their subsequent business success. They went on to sell orientalism—so popular at the fair—as entrepreneurs, merchants, and impresarios. Several of them offered exotic entertainments at Coney Island, in traveling carnivals, or on vaudeville stages, directly modeled on Midway shows. Others, like the Oussanis, opened Turkish smoking parlors. Still others sold oriental or Holy Land goods at great profit. Many of these men were then able to move into more “American” businesses like wholesaling dry goods, manufacturing garments, or becoming real estate entrepreneurs. Unlike the vast majority of Syrian immigrants who had to peddle for at least three years to save up enough money to open a business, these men’s capital was what they had learned at the great Chicago fair.