In an excerpt from my new book, Strangers in the West, we continue the travails of new Syrian immigrants who landed in New York harbor.

When a Syrian arrived at Castle Garden or Ellis Island, he or she was examined by various officials including emigration and health officers. This was the time when many were turned back. Although the authorities required the steamship companies to pay their return fare, they only took them back to their European port of embarkation, often leaving them stranded in Marseilles, Le Havre, or Liverpool. If they had the means, they would book another passage to New York or return to Syria. If not, they might settle in one of these ports and provide services to newer immigrants.

“Loathsome Disease”

The examinations were cursory but strict. The health exam, which determined whether the immigrant had a “loathsome disease” averaged about six seconds per passenger. My grandmother, almost a century after arriving at the age of seven, still talked about the terror invoked by the infamous “mark”—the mysterious symbol chalked on the immigrant’s back—that determined whether an immigrant was to be admitted, confined, or sent back. Trachoma was the most common reason people were sent back, followed by cholera, yellow fever, and leprosy.

“Likelihood of Becoming a Public Charge”

The characterization in the newspapers of Syrians as thieving beggars played out in the examination halls of the Emigration Commission. Over and over again, new immigrants were characterized as poverty-stricken, dirty or slothful—or all three—who could only be coming to this country to beg (which is how many people thought of peddling). Dozens were turned back on this pretext, whether or not they had money, the promise of a job, or a family member to vouch for them. The Syrians in New York learned to fight back. In several cases, already-wealthy Syrian businessmen appeared at the Barge Office to provide a bond for the incoming immigrants. Sometimes these gestures of help were offered as a kindness to relatives or friends, and sometimes they were schemes to enmesh the immigrant in a web of indebtedness to the businessman. In one case, the son of a prominent Syrian sued the Emigration Commission to show cause as to why a group of Syrians should be sent back. He lost the case, but several of the debarred were admitted later.

Many of these Syrians were indeed poor but by no means all. A significant number came with money or goods (which were invariably called “cheap trinkets” by the press) and began to peddle or set up businesses when they arrived. Those who came with nothing usually found a countryman to give them stock on credit—either notions or so-called “Holy Land goods”—and to whom the gave their loyalty until they were able to go out on their own. None became a “public charge.”

“Contract Labor”

The most vexing category of offense was that of “contract labor,” because it was so ill-defined. Taken from the Italian padrone system in which immigrants came to this country already contracted to an employer, it was regarded as a kind of indentured servitude by Americans but as a guarantee of work in a new land by the new immigrants. Newspapers and emigration officials visualized a vast Syrian conspiracy in which merchants contracted with would-be immigrants to come to this country to “beg” (i.e. peddle). These merchants supposedly had agents in Syria who would “lure” unsuspecting young men and women with promises of riches and then ensnare them in a trap of perpetual servitude. Much more likely was the story told by many of our grandparents of an informal web of relatives and friends who helped the immigrants pay for their passage, provided them with goods, and took a share of the profits in return. Almost everyone eventually saved enough money to strike out on their own, making a mockery of the idea of perpetual servitude.

Polygamy

None of the Syrian immigrants who came to this country in the nineteenth century came with more than one wife. Not only were the vast majority of immigrants Christian, but the few Muslims who came knew enough not to admit to being polygamous, even if they were. But just the fact that their faith sanctioned polygamy made these Muslims suspect, and some were debarred for that reason alone.

Even though these myriad stories imply that hundreds of Syrians were sent back every year, the Industrial Commission on Immigration reported that during the year 1900, a mere 0.41 percent (120) of Syrians who arrived were barred from entering the United States: 71 for poverty, 48 for disease, and only one for being a contract laborer. It may be that by 1900 the immigrants had become more savvy about the immigration process and were more frequently able to pass inspection, or it may be that the number of Syrians debarred was always small, at least compared to the number admitted.

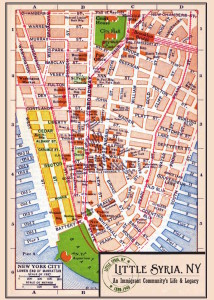

When the new immigrants walked up Washington Street from the Battery,where they first set foot on American soil, they would have heard Arabic on every side. Many of the storefronts had signs in Arabic in the windows; there were men smoking water pipes in the cafés; and many of the men and women walking through the streets looked much as they did at home, notwithstanding their westernized clothing. The smells coming from the restaurants must have been comfortingly familiar, especially after the weeks at sea in steerage. The new arrival knew he would be able to find a bed in a Syrian-owned boardinghouse, a Syrian meal, work of some sort, and if lucky, a friend or relative from his hometown to help him settle in.