The New York Syrian colony of the nineteenth century was centered on Washington Street on the lower west side of Manhattan and later in Brooklyn. But in reality, the New York community included a number of satellite towns in which Syrians lived, which were closely tied to New York City. The outliers felt that they were part of the colony, and the colonists felt the same about the outliers. There was frequent back and forth between the satellites and the city: New York manufacturers and wholesalers regularly visited their customers in nearby towns; peddlers’ suppliers came to New York to stock up; priests traveled to perform marriages and baptisms, or the residents would come to the city for those services; Syrian musical evenings or meetings were attended by those from outside New York. Some of the communities that had the closest relationship to the city are described here.

The Brickyards of Dutchess County

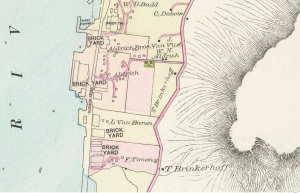

The brickyards of Dutchess County, located about fifty miles north of New York City, in places like Fishkill, Poughkeepsie, Rondout, and Dutchess Junction, employed more than a hundred Syrian workers in the nineteenth century. These yards supplied bricks to the booming construction industry in New York. Dutchess Junction was considered the center of this work, not only because of the five brickyards located there, but also because it was the site of the junction of two railroads, making easy access to New York City. Several Dutchess couples were married in New York City and had their babies baptized there. Their divorces were conducted in the New York City courts. New York Syrians considered Dutchess a suburb of the New York colony; as Muossa Daoud (who worked in the brickyards when he first arrived) said, “If work failed in the brickyard in Dutchess, they [the Syrians] would return to New York.”

New Jersey Silk Mills

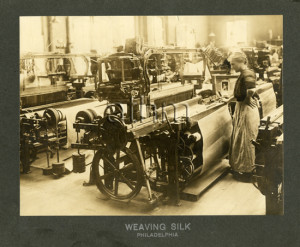

The Paterson, New Jersey, silk mills were infamous for their terrible work conditions and slave-like labor practices–a famous strike took place there in 1913–and dozens of Syrians worked under similar conditions in the Passaic, Summit, and Hoboken mills in the nineteenth century. Most of the silk factories in which the Syrians worked were owned by Americans, but some of the factories were taken over by Syrians in the twentieth century, including one in Hoboken. At first owned by the Gorayeb brothers, it was foreclosed on in 1906 by a Syrian bank and sold to another Syrian. The new owner was murdered ostensibly by the men who had lost the factory. As in many such cases, nothing came of the accusations. The Syrian laborers who worked in these mills went to New York to marry or baptize their children and attended church on Washington Street when they could.

Upstate New York

Almost every upstate town had a community of Syrians in the nineteenth century, including Albany (having about 40 Syrians), Binghamton (30), Buffalo (45), Geneva (25), Syracuse (30), and Utica (25). Most of the residents were new immigrants, either peddling around town and nearby farming communities, or employed by other Syrians, who had already opened stores. These latter maintained close ties to suppliers in New York City and traveled back and forth regularly, but most of the residents found New York too far to go and instead relied on local services rather than depending on New York. Conversely, many New York Syrians went upstate in the summers, either to peddle or to work as fruit pickers on the many farms. They became well acquainted with and at home in upstate resorts such as Richfield Springs (a favorite market for women selling oriental goods) and Niagara Falls.

The Boardwalk, Atlantic City

The Syrian community of Atlantic City, New Jersey, although dependent for customers on the town’s close proximity to Philadelphia, was also closely tied to New York City. Rather than laborers or peddlers, the Atlantic City Syrians were, from the very beginning, merchants, catering to the half-million visitors who thronged the beaches and Boardwalk every summer. The earliest Atlantic City shopkeepers were Abraham Samaha, brothers Fares and Elias Ferzan (“Ferzans’ Bazaar”), and E.F. Kettaneh, all of whom set up shops along the Boardwalk selling oriental goods in the early 1880s, soon after the Boardwalk was built. These merchants were as enterprising as their New York compatriots, importing their oriental goods directly from Syria.

These three shopkeepers, along with New York merchant John Abd-el-Nour, attended the Louisville (Kentucky) Expositions of 1883, 1884, and 1885, lending “oriental” color to what was primarily a showpiece for American commerce. Their booth was called, “The Pride of Damascus,” and in it, the merchants demonstrated silk weaving and sold oriental goods supposedly made on their looms. One reporter said, “This exhibit contains, doubtless, more genuine curiosities than any other display from any foreign country….” Samaha married a Kentucky girl and brought her back to Atlantic City, where they raised their children. He stayed on the Boardwalk until 1915, when he moved his family to Manhattan and opened a confectionery shop on Washington Street.

While Fares Ferzan attended the Louisville fair, his brother Elias minded the store in Atlantic City. After the Louisville fair was finished, Fares opened an oriental goods store in Kansas City and attended the Minneapolis Industrial Exposition of 1886, at which he demonstrated fine silk weaving and bragged about his family’s centuries-old skills in textile production. Although he talked to the reporters mainly about silk, he sold a fine example of a wool coat to the Smithsonian Institution in 1887.

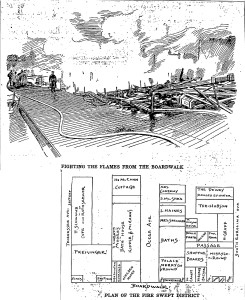

“Fighting the Fire from the Boardwalk,” 1898. Ferzans’ is halfway between Ocean Avenue and S. Carolina.

Ferzan was active in the New York colony: he married Sassool Maloof in the Maronite chapel at 81 Washington Street in 1894; arranged for the funerals of several men who had no family in New York; and provided extemporaneous poetry recitals at cultural evenings. Elias traveled the east coast selling oriental goods, and in 1894, the brothers opened stores in Providence, RI and St. Paul, MN, all the while maintaining their shop on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. In 1898, however, a devastating fire broke out on the Boardwalk, destroying Ferzans’ Bazaar, along with many other shops. The brothers packed it in and moved to Boston, opening a new oriental goods shop. Elias married there and raised a family, but we don’t know what happened to Fares; perhaps he and his wife went back to Syria.

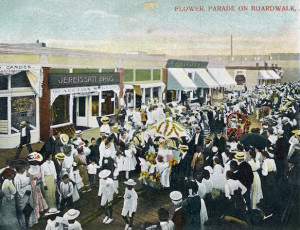

By 1900, other Syrians had replaced these pioneers on the Boardwalk, including Abdullah Karsa and his family (oriental goods), the brothers Amin, Salim and Najib Daher (a Syrian restaurant), Habib Nahass (oriental goods), John T. Haddad (groceries), Tannous Azeez (jewelry), the Jereissati Brothers (oriental rugs), Rasheed A. Moghabghab (oriental goods), and Mme. S. Moghabghab, who (along with her husband Salim) opened three retail women’s stores in Miami, New Hampshire, and Atlantic City, located in the posh Charlton Hotel.

Shops along the Boardwalk, Atlantic City, NJ, ca. 1900. The Jereissati Bros. whose shop is visible, were Syrian merchants.