There are more than 300,000 Chaldeans in America today, with large communities in Detroit and San Diego; in the nineteenth century, there were virtually none. The Chaldeans, sometimes called Assyrians or Nestorians, are Christians from Iraq and other Middle Eastern countries, who claim to be among the first Christian converts. The ancient language of the Chaldeans, Aramaic, has almost died out and been replaced, first by Arabic and now by English. The Oussani family from Baghdad were the first and only known Chaldeans to settle here in the nineteenth century.

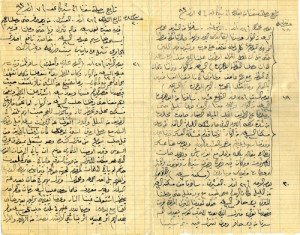

Joseph Oussani’s travel diary of journey from Baghdad to Marseille, 1893.

The family had been merchants and traders between Iraq and Persia for generations,[1] and four Oussani brothers worked in that trade with their father Tannous. He decided to send two of his sons to the Chicago world’s fair, which was to open in May of 1893. Word of the fair had spread all over the Middle East, and thousands of people headed to Chicago; the Middle East was probably the best represented region of the world.[2] Joseph, the eldest Oussani son, signed a contract with a group of Syrian investors to bring goods and persons “not exceeding twelve” to Chicago. Carrying forty trunks of goods and accompanied by a dozen Persians, Joseph left Baghdad on March 7. He traveled for thirty-eight days by camel caravan and ship to Marseilles, France, and finally landed in New York harbor on May 3.

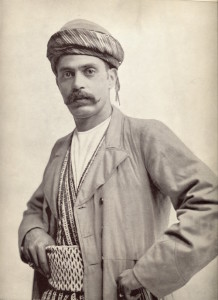

Yak Oussani at Chicago Fair, 1893.

The Columbian Fair was the largest world’s fair ever staged; more than twenty million people attended— a quarter of the entire U.S. population at that time. It consisted of two parts: the fair proper, in which each country and each state built a pavilion to show off its products, and the so-called Midway Plaisance, a mile-long promenade outside the fair, in which the real fun and real business took place. The Middle Eastern presence on the Midway was extensive, including the “Algerian and Tunisian Village,” “Moorish Palace,” “Street in Cairo,” “Turkish Village,” and the “Persian Palace,” the last built by the Oussanis. Each of these attractions presented a combination of entertainment, food, and goods for sale. Everyone who worked in these concessions was costumed in “native dress.” It was said that the Oussanis were disappointed by the attendance at the Persian Palace at first and decided to add some spice to the performances by importing can-can girls from Paris. People in the know began to call the place “The Persian Palace of Eros.”

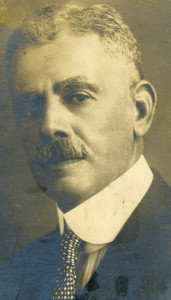

Joseph Oussani at Chicago Fair, 1893.

Whether the story is accurate or not, the Oussanis did make a success of the fair, because when the two brothers moved to New York after the fair closed in November, they set up two businesses: a tobacco and cigarette manufacturing business on Park Place near City Hall and a shop selling Oriental goods on East 23rd Street. In 1895, to boost their tobacco business, they founded what was probably the first Turkish smoking parlor in New York: the Cairo Café on West 29th Street. They decorated the place with Oriental furnishings, sold Turkish coffee and tea, and provided cigarettes or hookahs to the clients. The place quickly became a hotspot; young “swells” would drop in after the theater, drink liquor, which the Oussanis sold illegally in their parlor, and get into fights with the “Bedouin” bouncer. Just as the Oussanis had hoped and predicted, women too came in large numbers, lounging on the divans (despite their constricting Victorian clothing), smoking cigarettes, and chatting. Soon the brothers opened a second smoking parlor around the corner on Broadway and called it “The Chibouk” (a kind of long-stemmed Middle Eastern pipe). They prospered. By 1900, there were hundreds of “Turkish smoking parlors” in New York, all modeled after the Oussanis’.

Scandal, though, dogged them. Both places were vilified in the press, which called for them to be shut down. They were a regular target for the Society for Suppression of Vice. The police raided them often, and Joseph and his Irish wife, Margaret Shea, were hauled into court, only to be released after paying a modest fine. The couple were not only accused of selling liquor without a license, but charged with running a “disorderly house” (brothel) as well. Meanwhile, the Oussanis amassed a fortune.

Joseph Oussani marries Margaret Shea in New York, 1896.

“Sketches of Gay New York,” article about the Cairo Café, National Police Gazette, 1899.

Semiramis apartment building, 110th Street, New York, built by Joseph Oussani in 1901.

In 1900, Yak and Joseph dissolved their partnership; they sold off their oriental goods, Yak took over the tobacco business, and Joseph went into real estate (he already owned three buildings in Manhattan). They sold the smoking parlors to a Syrian entrepreneur, Nahmy Homsi. That same year, Joseph’s company built two apartment buildings in New York, which survive to this day: the Semiramis and the Zenobia, both on Central Park North. Semiramis and Zenobia are the names of two ancient Near Eastern queens. He kept a large apartment in the Semiramis, bought a house and land in Pocantico Hills in Westchester, on which he hoped to build a casino, owned a large mansion in Hastings-on-Hudson, and planted three hundred acres of grapes in Fresno, California. All of his houses were furnished with splendid oriental tables, carpets, brass lamps, and trinkets, many of which had come out of their original business on 23rd Street.

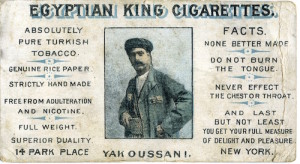

Advertising card for Egyptian Flower cigarettes, manufactured by Yak Oussani. Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, NY, 1901.

The rest of the Oussani family—three brothers, a sister, and their mother—came to join Joseph and Yak in 1900 (their father had died). Peter joined Joseph in the real estate and construction business, while John partnered with Yak. Gabriel Oussani, a Chaldean priest, taught and preached at St. Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers. Even after Yak died unexpectedly in 1903, John successfully carried on the cigarette business until the Depression. Joseph and Peter bought and sold real estate in Manhattan throughout the 1920s and 30s, buying foreclosed properties that they flipped for a profit. Joseph split his time between New York and California and became well-known on both coasts.

Despite their common language, the family had only tenuous links to the Syrian colony on the lower west side of Manhattan;[3] they were not only physically removed from the colony but had few dealings with them. But in the next generation, that link was strengthened when Joseph’s daughter Isabelle married the Syrian Nasri Fuleihan in a splendid wedding at the Hastings-on-Hudson mansion.

Notwithstanding his financial successes, Joseph’s personal life was tumultuous, with his second wife suing him for divorce on the grounds of adultery and several subsequent scandals. In 1934, Joseph was hit by a trolley in Hastings-on-Hudson and died of internal injuries. He and his first wife are interred in the stately mausoleum that Joseph erected at Calvary Cemetery in Queens.

[1] There were a great many Nestorians in Persia and it is likely that the Oussanis’ trading partners were from that group.

[2] Presbyterian missionaries in Syria lamented the departure of so many of their flock and condemned their “mercenary” motives for going.

[3] The Syrians lived near the Battery along Washington Street until they began moving to Brooklyn around 1900.

Read more about America’s first Arab immigrants in Strangers in the West.