Even today, successful women entrepreneurs are as rare as hen’s teeth. Imagine what it took for a nineteenth century woman from a conservative Arab immigrant community to become one of the premier jewelers in New York. Marie El-Khoury was that woman.

The Azeez Family

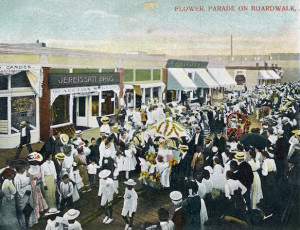

They arrived in New York harbor on June 8, 1891: Tannous Azeez, his wife Julia Tabet, and daughters Alice and Marie. Like almost all early Syrian immigrants, they settled in the Syrian colony on the lower west side of Manhattan, a short walk from where they disembarked. Tannous perhaps peddled at first like most of his compatriots, but he may have arrived with a supply of gemstones, because he quickly set up a jewelry business at their home at 37 Washington Street. Many Syrians called themselves jewelers, but their “jewels” were cheap trinkets made of glass and base metal. Azeez was different; it seems he was an experienced gem dealer and cutter and began to import and sell semi-precious stones quite early, becoming known especially for his stock of Persian turquoise. Azeez moved his family to Brooklyn in 1894—one of the earliest Syrians to settle there—but kept his shop on Washington Street until 1900, when he established his eponymous jewelry store on the Boardwalk in Atlantic City, New Jersey, “The Shop of T. Azeez.” There were about a dozen other Syrians who had shops on the Boardwalk selling oriental goods, but none equaled the quality of T. Azeez. The family moved to Atlantic City in 1901 and made their home behind the store.

Shops along the Boardwalk, Atlantic City, NJ, ca. 1900. The Jereissati Bros. whose shop is visible, were Syrian merchants.

Alice Azeez

Both daughters were unusual for their time and culture. Alice was sixteen when they arrived, and she immediately began to give talks dressed in “native costume” at churches and halls around New York state, for which she may have been paid a stipend by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions. She had studied with the American missionary H.H. Jessup in Beirut and was fluent in English and reputedly five other languages. Only six months after she arrived, two hundred people attended one of her lectures. She became a minor celebrity by feeding the American press exotic (and fabricated) stories: she was a Syrian princess named “Fannitza Abdul Sultana Nalide,” a member of one of the wealthiest families in Beirut. She had enrolled at Harvard Annex (the forerunner of Radcliffe) in order to study medicine and the “Occidental ways of doing things,” and she planned to use this knowledge to help her (benighted) fellow countrywomen. There is no record of her having attended Harvard or of her helping her countrywomen. She also claimed to have written a book about her life in America; launched a literary magazine; and in the most egregious lie of all, she told reporters that her father had been killed in the massacres in Syria in 1860, when of course he was alive and well and selling jewelry in New York.

None of these stories had legs and they quickly disappeared from her repertoire. They were, though, symptomatic of a very real drive to make her fortune, and she did try many things in addition to her lecturing: she sold Near Eastern antiquities, which she may have acquired from Azeez Khayat, a Syrian dealer, to various museums; filed patents for a fabric design and a fountain attachment that sprayed water in the shape of a flower; and tried to start a nursery in the Bronx with plants imported from Lebanon. She was not only openly ambitious but bragged about her accomplishments (both real and imaginary), traits not often displayed by young women at that time, especially Syrian women. One charmed reporter asserted that “there are very few women of her age that can do more things to make money, or do them better.” Whether she ever made a living is not clear. She continued to lecture and by 1910, was known as “Sitte [Madame] A. Azeez.” She never married and lived with her mother and sister until her death.

Marie, a True Pioneer

Marie had a more respectable but also more spectacular career. She went to high school at the Methodist-run Drew Seminary in Carmel, New York, and then became the first Syrian girl to attend college in the United States, graduating in 1900 at the age of seventeen from Washington College for Ladies in Washington, DC. What an amazing man Tannous must have been to allow his daughter to go to college so far from home! She was also the first Syrian woman journalist in America, contributing articles even before she graduated from college to the Arabic-language newspapers Al Hoda, Al Ayyam, and Mira’at al Gharb. Her earliest article was a series on the history of Syrians in America, published in 1899. She also apparently wrote for English-language papers. An oblique reference in Al Hoda seems to indicate that she founded an English-language woman’s magazine in 1898, and if true, it would be another first, but there is no other information about it.

In 1902, she married a fellow journalist named Esau el-Khoury, who was the publisher of a magazine called Al Da’ira al Adabiya (The Literary Circle), but he died tragically at the age of twenty-five in 1904. That same year, her father’s shop was destroyed in a large fire that took dozens of other shops on the Boardwalk, and the business was nearly wiped out. Tannous died less than a year later of complications resulting from surgery. He was fifty-four. Marie, with her husband and father dead, realized it would fall upon her to support her mother and her sister (as well as herself), and she gave up journalism to take over her father’s business; she had learned the jewelry trade at his side. Just as she was beginning to rebuild from the fire, the shop was burglarized and everything of value taken.

The Little Shop of T. Azeez

Marie was undaunted. She borrowed money from several of her father’s friends and was able to restock and keep the shop open. She continued her father’s practice of working with precious and semi-precious stones and taught herself jewelry design, at which she became a master. Her efforts were so successful that she was able to pay back the loans in record time and support her family. In about 1915 she moved the shop to Manhattan, to 561 Fifth Avenue, at Forty-sixth Street—the only Syrian merchant that far uptown—calling it “The Little Shop of T. Azeez” in honor of her father. She brought her mother and sister to live with her in a duplex apartment in the “exclusive” newly-built residential Hotel Seymour on Forty-fourth Street.

Her shop’s tagline was “Individuality in Jewels,” and she pioneered the idea of jewelry designs that were adaptable to an individual’s taste: a customer could choose the color of beads or the number of pearls in a necklace, or wear a piece as a brooch, pendant, or shoe ornament. In the thirties, Marie offered clients the opportunity to look at new designs in wax and redesign them to suit.

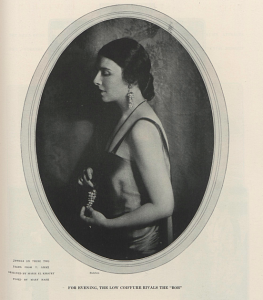

“If you put either enough money or enough thought or both into one ornament, it will repay you.”

She became a jeweler to the rich and famous, competing with such behemoths as Tiffany and Cartier. She advertised regularly in Vogue and the New Yorker, and they reciprocated by featuring her jewelry on their models or in their recommendations for Christmas gifts. A 1940 New Yorker feature described “a clip pin made of two fluttering butterfly wings studded with tremendous marquise aquamarines beautifully set in diamonds and platinum [that] comes apart at the centre and makes two clips. Fragile and lovely; $4,500.” She not only designed her own innovative jewelry, but she commissioned jewelry from some of the finest modernist designers of the time.

Her pronouncements on couture, culture, and cuisine were reported in newspapers and fashion magazines. Her dinner parties were legendary: she often served meals in which every course was the color of a gemstone. One night, the menu featured a lamb stuffed with a turkey, which was stuffed in turn with a chicken, a golden pheasant, and finally a humming bird.

Her shop stayed at Forty-sixth and Fifth for more than two decades and then moved northward to progressively smaller venues, until she retired in 1955. She died in 1957 at the age of 74. A thorough search of the internet did not turn up a single piece of her jewelry, either because her pieces were unsigned or because the owners’ descendants still treasure them. Although she built her success in the world of upper-class New York society, Marie’s lasting legacy is tied to her roots: she endowed a scholarship fund in fine arts at the American University of Beirut.