Note: This article was written by my friend Robert Goodhouse, a descendant of the Syrian-American publisher, Najeeb Diab. He lives in Dubai and is a Vice President of Rapiscan.

-Linda Jacobs

One hundred years ago Moslems and Christians from the Middle East joined in a historic political meeting that might have changed the face of the Middle East.

In Paris in 1913, eleven Muslims, eleven Christians, and one Jew, most of them from today’s Iraq and Syria, gathered for five days to develop a program that would lead toArab independence from Turkey, a program based on a secular federal process, rather than religious affiliation. It was a revolutionary approach. Although the majority of delegates were Middle-East based, three early Syrian immigrants to the United States, all living in New York, also participated: Najeeb Diab and Elias Macksoud represented the Syrian Orthodox, and Naoum Mokarzel represented the Maronites. As Diab wrote “… the ranks [are closed] between Moslem and Christians…. [and we have] all lost confidence in the Turks.”

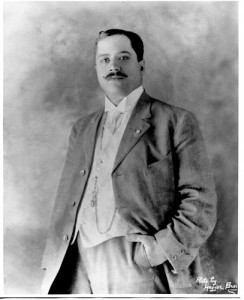

Diab, born in Mt. Lebanon in 1870, emigrated via Egypt to New York in 1893. He served as editor of America’s first Arabic paper, Kawkab America, and then started his own paper, Meraat ul-Gharb (Mirror of the West) in 1899, which he intended, he said, “…to speak for Arabism.” The paper offered political views but also had a literary bent; many Arab émigré writers and poets published their first pieces in Diab’s paper.

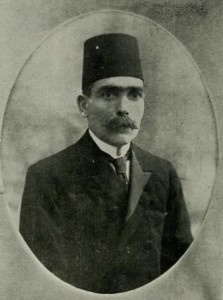

Diab also led the New York-based United Syrian Society, and through it, and through editorials in Meraat, he collected dozens of supporting telegrams for the Congress from Arab émigrés as far afield as “The Syrian Reform Society of Waynoka, Oklahoma” (population 1,850). At the Congress, Diab and Macksoud met with a representative of a leading Muslim activist, Rafiq al Azm, who had been exiled to Cairo, where he joined other Islamic reformers in demanding both an overhaul of Islamic approaches to modernization and an independent voice for Arabs in the Ottoman Empire. It was in Paris that Diab’s and al Azm’s views coincided. The Congress, which was sponsored by an illegal independence group called Al Fatat (pictured above) was given legitimacy by al Azm’s participation.

The Congress’s ten resolutions were approved, but then sadly–and predictably–substantially watered down by the Ottoman Government. France, for its part, used the Paris location of the Congress to hold some individual meetings and shore up its “friendship” with certain of the delegates (among them Naoum Mokarzel), further dividing political loyalties and encouraging political separatism. And the First World War made the whole idea of independence moot as a victorious Europe pursued its own interests in the Middle East.

Yet for five days in June 1913, an Arab-American Christian worked together with his Arab Muslim counterparts to plan and articulate the basis of a new Middle East. And now more than one hundred years later, only a few vestiges of pan-Arabism remain, such as the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council. Militant Islam, and the absence of substantive Muslim-Christian dialogue make us think that Ten-Resolution plan may not have been such a bad idea.