We’ve all heard the story: “My grandfather came over from the old country with nothing but the clothes on his back. His uncle [or cousin or friend], God bless him, supplied him with a shenta [pack or satchel] and goods on credit and sent him out to peddle. He couldn’t speak a word of English. After a few years of peddling—oh the funny stories my grandfather told about those years!—he was able to settle down and start his own business. He married a Syrian girl, had a family, and became enormously successful: he bought a large house in Brooklyn, employed servants and a chauffeur, sent his children to college, and entertained the Syrian intelligentsia at his home. When he died, his funeral was the largest ever seen in the Syrian community.” I don’t know how many times I’ve heard this story repeated in my family and by other descendants of the Syrian colonists. I’ve never heard anyone say, “My grandfather came over with nothing and died with nothing.” Have you?

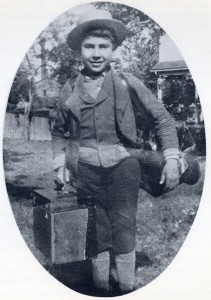

A young peddler: B.K. Forzly with his notions case, 1898.

This is the myth of the Syrian immigrant. It is not that different from other immigrant myths except perhaps in being a little more pervasive in our culture than others. Like all myths, it has a kernel of truth. The early Syrian immigrants—those who came to America in the nineteenth century—were remarkable men and women: courageous, entrepreneurial, and hard-working. A majority of them did begin as peddlers and worked their way up to become small or large business owners. Many did live in spacious homes near Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. And many, when they died, had large funeral services.

But what about those who did not fit the myth? First of all, there were dozens of immigrants who were not poor when they arrived. They came with a nest egg and at least a smattering of western education. A good number of them had graduated from the American University of Beirut. They had a leg up on other immigrants and were able to start immediately in business, without having to peddle. These men (there were no women in this group) set up as merchants, manufacturers, or importers, founded newspapers, or set up medical practices; they were able to succeed much more quickly than their compatriots who came with nothing.

And then there were those who, for me, are the most interesting of the immigrants: those who came with nothing and never made more than a modest living, if that. We know much less about these men and women, not only because our families rarely speak of them, but because they leave fewer documents for us to study. Some of those who didn’t make it went back to Syria and so disappeared from view as far as we are concerned. The others—those who stayed and eked out a living as best they could—are almost as unknowable as the ones who left. Although all became more prosperous than they had been in their first years in the colony, where the living conditions were deplorable, many struggled to make ends meet and many of those who had been initially successful suffered bankruptcy.

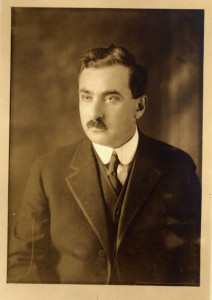

FM Jabara, 1908.

My two grandfathers illustrate these two contradictory trajectories. My maternal grandfather, Fayad Jabara, came to the United States from Syria in 1902, with no money, no English, and no prospects, but other men from his village had come before him, so he was not friendless when he arrived. He peddled for three years and was able to save enough money to go into business making ladies’ housecoats (called in those days “dressing sacques” and “kimonos”) with a man from his village. After three years, they went their separate ways, each starting his own business. With two of his brothers, my grandfather began to manufacture and import linen towels, tablecloths, and dresser scarves. The company, “F.M. Jabara and Brothers,” had agents at factories in Ireland, England, Portugal, Italy, and China and sold their goods to “trousseau shops” all over the United States. My grandfather married, bought a brownstone house in Brooklyn, had five children all of whom he educated, and when he died in 1949, his funeral cortege was huge.

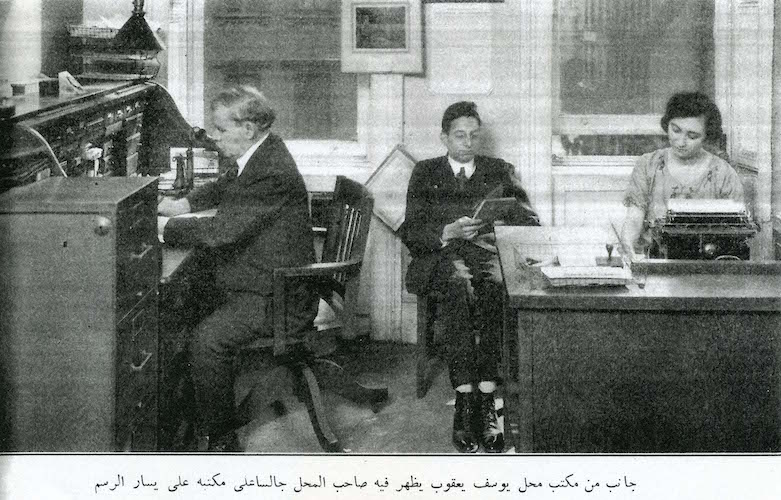

My father’s father, on the other hand, led a completely different life. He came to America much earlier—in 1888—apparently having been in trouble with the authorities in Syria. A relative in New York gave him his first shenta and he traveled around the country selling until he ran out of goods and money. He met up with his brother in Denver who owned a confectionery shop, but he stayed less than a year (and if we can believe the newspapers, he got into trouble there as well). Then he opened a series of small shops (fruit stands or confectionery stores) in various cities, all of which failed. He returned east and met a young Syrian girl, whom he married in New York in 1897. The marriage did not stop him continually searching for a secure living; each of their first five children was born in a different state. Finally after almost two decades of constant traveling, he was able to settle down, having become the New York agent of the Geneva Cutlery Company, which made straight razors. He, a clerk, and a secretary worked out of a small office in Manhattan, but the family lived in a rented house near Prospect Park, Brooklyn. After a short stretch of (modest) prosperity, he went bankrupt when the safety razor was invented. He became an invalid and died in debt in 1933. His funeral was small: three cars and a hearse.

His story would have been lost like so many others in his position except for the fact that two of his daughters were already successful lingerie designers who paid off their father’s debts, supported the family through the Depression, and put their brothers through school. One of those brothers, my father, ended up a successful engineer, business owner, and philanthropist, and his success reflected on his father, partially rescuing him from obscurity. I have done the rest.

These stories only show what we know to be true: that there are disparities in wealth, ability, and luck in every community, and the Syrians were no exception. We need to wrest every Syrian story from public documents and family archives and be ready to relate the bitter and the sweet.